In an interview with the AFP news agency this week, Pietro Barabaschi, Director-General of ITER, said it may be years before the International Thermonuclear Experimental Reactor (ITER), currently under development in France, produces any useful energy.

First launched in southern France in the 1980s, the project was designed to produce commercial electricity through nuclear fusion. It had been anticipated it would become a major large-scale source of carbon-free power by 2025.

Barabaschi has now conceded that the startup date, “wasn’t realistic in the first place,” and that now two new challenges impeding the project have emerged.

The first of the two new challenges is that the measurements for the joints of blocks which must be welded together for the reactor’s chamber have turned out to be wrongly calculated. The second issue is the recent discovery of traces of corrosion in a thermal shield which is required to contain the heat required to sustain the nuclear fusion reaction.

Barabaschi noted that fixing these issues “is not a question of weeks, but months, even years.”

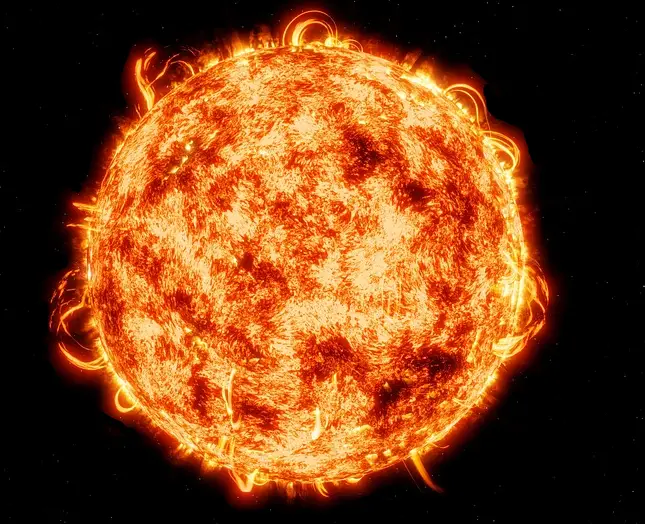

The fusion process forces together light atomic nuclei in a heated plasma, which is contained within a donut-shaped device called a tokamak. If it can be harnessed, fusion promises a safe, environmentally friendly source of almost limitless electricity.

ITER was created in 1985 after US President Ronald Reagan held a summit with Russian leader Mikhail Gorbachev. Over the years since however the project has faced a series of technical problems and cost overruns. Currently it has evolved into a joint project between companies from China, the EU, India, Japan, South Korea, Russia and the US.

Moscow continues to remain involved in ITER despite the geopolitical situation surrounding the Ukraine conflict, and the sanctions the West has levied against the country. Russia has even supplied the giant magnet required to construct the tokamak.

The goal of the ITER tokamak reactor project is to produce the world’s largest and most powerful fusion device.